The Moravian mission at Shekomeko was founded in 1740 by Christian Henry Rauch to convert the Mahican Indians in eastern New York. Today the location of the Mahican village is marked by the monument, above, at Pine Plains in Dutchess Co., NY.

In the late 1730s the Moravian Church established their first missionary efforts in North America near Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. The Moravian Church had been founded during the 15th century in Bohemia and Moravia. Following almost total destruction in the Thirty Years’ War and Counter Reformation, it had been revived in the 1720s.

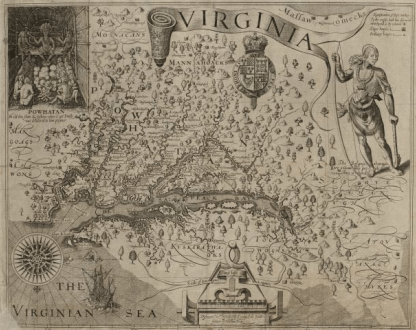

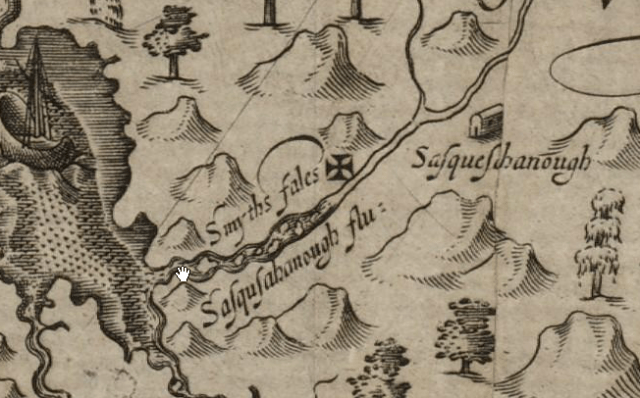

The Moravian Bishop August Gottlieb Spangenberg sent Christian Henry Rauch to New York City in 1740 on a mission to preach and convert any Native peoples he could find. Rauch arrived in New York on July 16, 1740 and met with a delegation of Mahican Indians to settle land issues. The Mahicans were an Algonquian tribe and branch of the Lenni Lenape or Delaware Nation who populated the east bank of the Hudson River in what is today eastern Dutchess County, New York, and western Connecticut.

Rauch convinced the delegation of his serious intention to instruct and teach them and Mahican Chiefs Tschoop and Shabash invited Rauch to visit their Dutchess County village. In September 1740 they led him through the unbroken wilderness to Shekomeko. There, Rauch established a Moravian mission and the two Indians chiefs were converted to the Moravian faith. In January 1742, Rauch accompanied Shabash, Seim, and Kiop on a journey to the Pennsylvania community for their baptism. Rauch’s first convert, Chief Tschoop, was lame and unable to make the journey. Upon their baptism the three were given the Christian names of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. After the group returned to Shekomeko, Tschoop was baptized as John on April 16, 1742.

By summer 1742, Shekomeko was established as the first Native Christian congregation in America.

On March 13, 1743, the distribution of Holy Communion marked a milestone in the development of the Indian congregation. In July 1743, a Moravian chapel was built and dedicated at Shekomeko. By the end of 1743, the congregation of baptized Indians numbered 63. Two satellite missionary outposts were established in Kent, Connecticut and on the New York – Connecticut border.

The increasing Moravian influence and success in defending their burgeoning following became disturbing to the region’s white colonists. False rumors of atrocities were spread, some fearful settlers had left their farms and the authorities were petitioned to intervene. Resentment by European settlers in the area quickly grew. The Moravian missionaries exposed traders illegally selling alcohol to the Native people and provided legal advice that kept them from being cheated. Many whites resented the missionaries interfering with “nature taking its course.”

The Moravian missionaries were repeatedly detained, interrogated, fined and released. Governor George Clinton summoned the Moravians to account for their missionary activities. Alleged to be Papist and conspiring with the outlawed Roman Catholic order of Jesuits, the Moravians successfully defended themselves and were exonerated when no link to the Jesuits could be found. However, they were admonished to cause no further suspicions.

The settlers’ enmity for the Moravians continued to grow. They persisted to oppose the Shekomeko mission and were determined to eradicate it. A law was enacted on September 21, 1744 forbidding anyone from residing with Indians in order to Christianize them.

The Moravian mission was finally doomed when the provincial assembly adopted a law on September 22, 1744 that required anyone choosing to live among the Indians to take an Oath to the Crown, obtain consent of the council and obtain a license from the Governor to do so; Moravian religious principles forbade taking oaths.

On October 27, 1744 the governor ordered the Moravian missionaries to “desist from further teaching and depart the province”. Then on December 15, 1744, the sheriff and three peace officers of Dutchess County appeared at Shekomeko under orders from Governor Clinton to give the missionaries notice to cease their teachings. The Moravian leaders were summoned to appear in court at Poughkeepsie.

The Moravians missionary venture was maintained sporadically for several years. In 1746 area settlers petitioned the governor to issue to them a warrant authorizing the killing of Shekomeko Indians. While the petition was not granted, upon hearing about the call for their extermination, the last ten families of 44 persons, all that remained of the original 8,000 member tribe 100 years before, left Shekomeko and dispersed, taking another step towards extinction.

Some sought refuge in nearby Connecticut, while others traveled to Pennsylvania to be closer to the established Moravian settlements there.

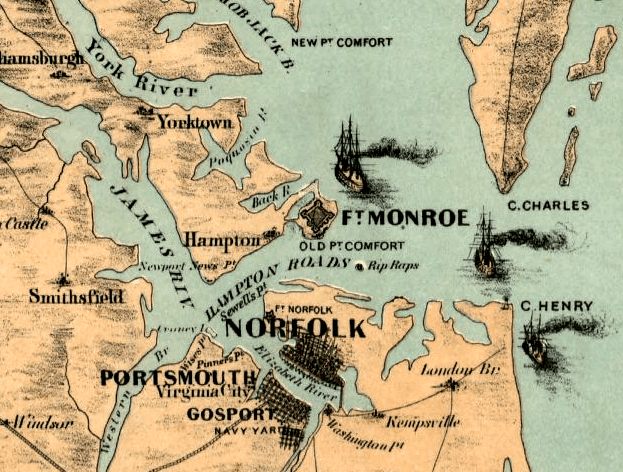

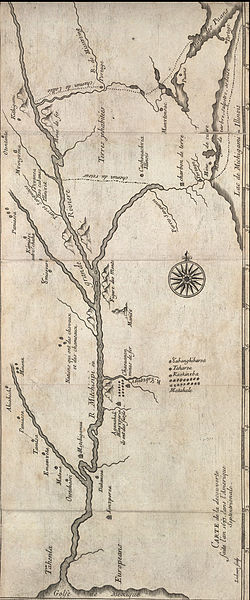

Ten families of 44 persons total arrived in Bethlehem, PA in April, 1746. However, because an Indian settlement could not be supported so close to an existing town, the Brethren bought land for the Indians at the confluence of the Mahony and Leeha rivers, about 30 miles distant which they named Gnadenheutten. Other Indians joined them and they eventually grew to a community of 500.

This land on the Mahoning being impoverished, and other circumstances requiring a change, the inhabitants of Gnaden-Huetten removed to the north side of the Lehigh. The dwellings were removed, and a new chapel was built, in June 1754. The place was called New Gnaden-Huetten. It stood where Weissport now is. The dwellings were so placed that the Mohicans lived on one side and the Delawares on the other side of the street.

But this wasn’t the end of the road for the Indians. During the Revolutionary War, in September 1781, British-allied Indians, primarily Wyandot and Lenape, forced the Christian Indians and missionaries from the Moravian villages. They took them further west toward Lake Erie to a new village, called “Captive Town”, on the Sandusky River.

The British took the missionaries David Zeisberger and John Heckewelder under guard back to Detroit, where they tried the two men on charges of treason. The British suspected them of providing military intelligence to the American garrison at Fort Pitt. The missionaries were acquitted. (Historians have established Zeisberger and Heckewelder did keep the Americans informed of the movements of the British and their Indian allies.)

The Indians at Captive Town were going hungry because of insufficient rations. In February 1782, more than 100 returned to their old Moravian villages to harvest the crops and collect stored food they had been forced to leave behind. The frontier war was still raging. In early March 1782, the Lenape were surprised by a raiding party of 160 Pennsylvania militia led by Lieutenant Colonel David Williamson. The militia rounded up the Christian Lenape and accused them of taking part in raids into Pennsylvania. Although the Lenape denied the charges, the militia held a council and voted to kill them. Refusing to take part, some militiamen left the area. One of those who opposed the killing of the Moravians was Obadiah Holmes, Jr. Among his observations of the incident was that “one Nathan Rollins & brother had had a father & uncle killed took the lead in murdering the Indians, …& Nathan Rollins had tomahawked nineteen of the poor Moravians, & after it was over he sat down & cried, & said it was no satisfaction for the loss of his father & uncle after all”. After the Lenape were told of the vote, they spent the night praying and singing hymns.

The next morning on 8 March, the militia tied the Indians, stunned them with mallet blows to the head, and killed them with fatal scalping cuts. In all, the militia murdered and scalped 28 men, 29 women, and 39 children. They piled the bodies in the mission buildings and burned the village down. They also burned the other abandoned Moravian villages. Two Indian boys, one of whom had been scalped, survived to tell of the massacre.

The militia collected the remains of the Lenape and buried them in a mound on the southern side of the village. Before burning the villages, they had looted, gathering plunder which they needed 80 horses to carry: furs for trade, pewter, tea sets, clothing, everything the people held.

Although there was outrage over the massacre, no criminal charges were ever filed. However, the lesson was neither lost on the Indians, nor forgotten.

In 1810, Tecumseh reminded William Henry Harrison, “You recall the time when the Jesus Indians of the Delawares lived near the Americans, and had confidence in their promises of friendship, and thought they were secure, yet the Americans murdered all the men, women, and children, even as they prayed to Jesus?”

A cabin and cooper’s shop, along with a monument have now been reconstructed on the site of the massacre in Gnadenhutten, Ohio, and the location is on the National Register of Historic Places.