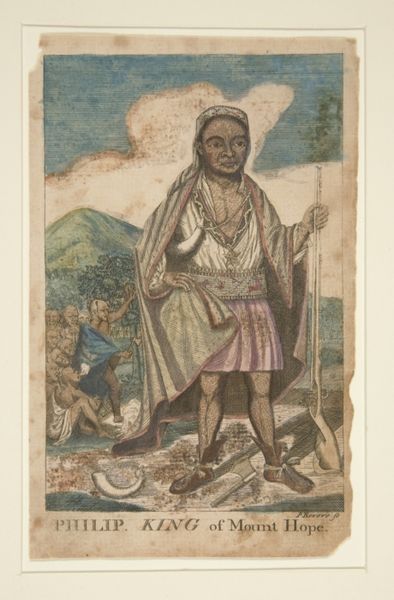

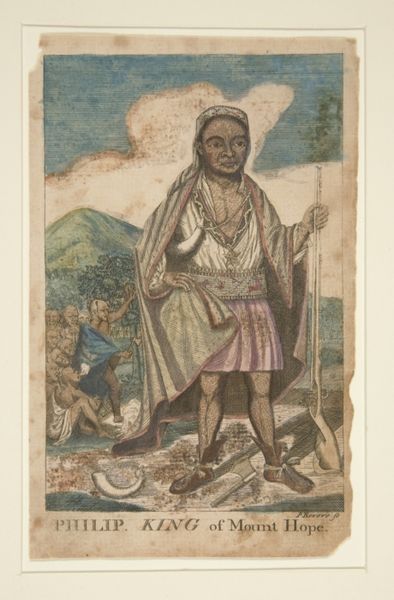

King Philip’s War was sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom’s War, or Metacom’s Rebellion and was an armed conflict between Native American inhabitants of present-day southern New England, English colonists and their Native American allies in 1675–76. The war is named after the main leader of the Native American side, Metacomet, known to the English as “King Philip”.

Plymouth, Massachusetts, was established in 1620 with significant early help from Native Americans, particularly Squanto and Massasoit, Metacomet’s father and chief of the Wampanoag tribe. The building of towns such as Windsor, Connecticut (est. 1633), Hartford, Connecticut (est. 1636), Springfield, Massachusetts (est. 1636), and Northampton, Massachusetts (est. 1654), on the Connecticut River and towns such as Providence, Rhode Island, on Narragansett Bay (est. 1636), progressively encroached on traditional Native American territories.

Throughout the Northeast, the Native Americans had suffered severe population losses due to pandemics of smallpox, spotted fever, typhoid and measles, infectious diseases carried by European fishermen, starting in about 1618, two years before the first colony at Plymouth had been settled. Shifting alliances among the different Algonquian peoples, represented by leaders such as Massasoit, Sassacus, Uncas and Ninigret, and the colonial polities negotiated a troubled peace for several decades. In the photo below, this boulder now known as King Philip’s Seat was a location for meetings.

For almost half a century after the colonists’ arrival, Massasoit of the Wampanoag had maintained an uneasy alliance with the English to benefit from their trade goods and as a counter-weight to his tribe’s traditional enemies, the Pequot, Narragansett, and the Mohegan. Massasoit had to accept colonial incursion into Wampanoag territory as well as English political interference with his tribe. Maintaining good relations with the English became increasingly difficult, as the English colonists continued pressuring the Indians to buy land for new towns.

Prior to King Philip’s War, tensions fluctuated between different groups of Native Americans and the colonists, but relations were generally peaceful. As the colonists’ small population of a few thousand grew larger over time and the number of their towns increased, the Wampanoag, Nipmuck, Narragansett, Mohegan, Pequot, and other small tribes were each treated individually (many were traditional enemies of each other) by the English colonial officials of Rhode Island, Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut and the New Haven colony. As their population increased, the New Englanders continued to expand their settlements along the region’s coastal plain and up the Connecticut River valley. By 1675 they had even established a few small towns in the interior between Boston and the Connecticut River settlements.

Tensions escalated and the war itself actually started almost accidentally, certainly not intentionally, but before long, it has spiraled into a full scale war between the 80,000 English settlers and the 10,000 or so Indians.

John Sassamon, a Native American Christian convert (“Praying Indian”) and early Harvard graduate, translator, and adviser to Metacomet, was a figure in the outbreak of the war. He told the governor of Plymouth Colony that Metacomet, King Philip, was intending to gather allies for Native American attacks on widely dispersed colonial settlements.

King Philip was brought before a public court to answer to the rumors, and after the court officials admitted they had no proof, they warned him that any other rumors—baseless or otherwise—would result in their confiscating Wampanoag land and guns. Not long after, Sassamon was murdered and his body was found in the ice-covered Assawompset Pond.

On the testimony of a Native American witness, the Plymouth Colony officials arrested three Wampanoag, who included one of Metacomet’s counselors. A jury, among whom were six Indian elders, convicted the men of Sassamon’s murder. The men were executed by hanging on June 8, 1675, at Plymouth. Some Wampanoag believed that both the trial and the court’s sentence infringed on Wampanoag sovereignty.

John Sassamon, a Native American Christian convert (“Praying Indian”) and early Harvard graduate, translator, and adviser to Metacomet, was a figure in the outbreak of the war. He told the governor of Plymouth Colony that Metacomet was intending to gather allies for Native American attacks on widely dispersed colonial settlements.

King Philip was brought before a public court to answer to the rumors, and after the court officials admitted they had no proof, they warned him that any other rumors—baseless or otherwise—would result in their confiscating Wampanoag land and guns. Not long after, Sassamon was murdered and his body was found in the ice-covered Assawompset Pond.

On the testimony of a Native American witness, the Plymouth Colony officials arrested three Wampanoag, who included one of Metacomet’s counselors. A jury, among whom were six Indian elders, convicted the men of Sassamon’s murder. The men were executed by hanging on June 8, 1675, at Plymouth. Some Wampanoag believed that both the trial and the court’s sentence infringed on Wampanoag sovereignty.

In response to the trial and executions, on June 20, 1675, a band of Pokanoket, possibly without Metacomet’s approval, attacked several isolated homesteads in the small Plymouth colony settlement of Swansea. Laying siege to the town, they destroyed it five days later and killed several people.

On June 27, 1675, a full eclipse of the moon occurred in the New England area. Various tribes in New England looked at it as a good omen for attacking the colonists.

Officials from the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies responded quickly to the attacks on Swansea; on June 28 they sent a punitive military expedition that destroyed the Wampanoag town at Mount Hope (modern Bristol, Rhode Island).

The war quickly spread, and soon involved the Podunk and Nipmuck tribes. During the summer of 1675, the Native Americans attacked several towns.

The New England Confederation, comprising the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Plymouth Colony, New Haven Colony and Connecticut Colony, declared war on the Native Americans on September 9, 1675. The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, settled mostly by Puritan dissidents, tried to remain mostly neutral, but like the Narragansett they were dragged inexorably into the conflict.

With these actions, a full scale war was indeed underway.

King Philip was shot and killed by an Indian named John Alderman on August 12, 1676. King Philip was beheaded, then drawn and quartered (a traditional treatment of criminals in this era). His head was displayed in Plymouth for twenty years. The stone below marks the location of King Philip’s death in Miery Swamp in Mounty Hope, Rhode Island.

King Philip’s head was secreted away by a colonial family that was friendly to him. The Leonard family kept King Philip’s head for many generations, before giving it to his descendants.

The war in the south largely ended with Metacom’s death. Over 600 colonists and 3,000 Native Americans had died, including several hundred native captives who were tried and executed or enslaved and sold in Bermuda. The majority of the dead Native Americans and the New England colonials died as the result of disease, which was typical of all wars in this era.

Those sent to Bermuda included Metacom’s son (and also, according to Bermudian tradition, his wife). A sizable number of Bermudians today claim ancestry from these exiles. Members of the Sachem’s extended family were placed for safekeeping among colonists in Rhode Island and eastern Connecticut. Other survivors joined western and northern tribes and refugee communities as captives or tribal members. Some of the Indian refugees would return on occasion to southern New England.

The Narragansett, Wampanoag, Podunk, Nipmuck, and several smaller bands were virtually eliminated as organized bands and even the powerful Mohegans were greatly weakened.

King Philips war was the single greatest calamity to occur in seventeenth-century New England. In little over a year, twelve of the region’s towns were destroyed and many more damaged, its economy was all but ruined, and much of its population was killed, including one-tenth of all men available for military service. Proportionately, it was one of the bloodiest and costliest wars in the history of North America. More than half of New England’s towns were assaulted by Native American warriors.

Conversely, about one third of the entire Indian population was killed, their villages destroyed, and the remainder who the colonists believed to have been involved where caught, killed or shipped into slavery in Bermuda. Some Indians did not fight against the colonists but fought with them, and those Indians were spared. This war was not only devastating to the Native population, but divisive as well. There were no winners, but the Native people lost more than anyone else, individually and as tribes.