The Cobell Case, known my many different names, was a class action suit filed by Native American representatives against two departments of the United States government. The plaintiffs claim that the U.S. government has incorrectly accounted for the income from Indian trust assets, which are legally owned by the Department of the Interior, but held in trust for individual Native Americans (the beneficial owners). The case was filed in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia. The original complaint asserted no claims for mismanagement of the trust assets, since such claims could only properly be asserted in the United States Court of Federal Claims.

The case is sometimes reported as the largest class-action lawsuit against the U.S. in history, but the basis for this claim is a matter of dispute. Plaintiffs contend that the number of class members is around 500,000, while defendants maintain it is closer to 250,000. The potential liability of the U.S. government in the case is also disputed: plaintiffs have suggested a figure as high as $176 billion, and defendants have suggested a number in the low millions, at most.

The case was settled for $3.4 billion in 2009, with $1.4 billion going to the plaintiffs and $2 billion allocated to repurchase land that was distributed under the Dawes Act and return it to communal tribal ownership. A documentary movie was made about this landmark case.

However, the most interesting part of this suit is the ownership of the Reservation land and the relationship between the government, the tribes and the individuals involved.

The history of the Indian trust is inseparable from the larger context of the Federal government’s relationship with American Indians, and the policies that were promulgated as that relationship evolved. At its core, the Indian trust is an artifact of a nineteenth-century Federal policy and its current form bears the imprint of subsequent policy evolutions.

During the late 1800s, Congress and the Executive branch believed that the best way to foster assimilation of Indians was to “introduce among the Indians the customs and pursuits of civilized life and gradually absorb them into the mass of our citizens.”

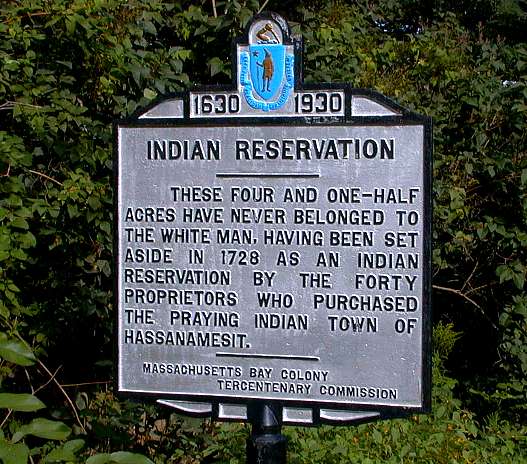

Under the General Allotment Act of 1887 (the Dawes Act), tribal lands were divided and assigned to heads of households as individually owned parcels 40–160 acres (0.16–0.65 km2) in size. The Dawes Rolls are the records of the members of each tribe who were registered at the time. The total land area that was allotted was small compared to the amount of land that had been held communally by tribes in their reservations at the passage of the Act. The government declared Indian lands remaining after allotment as “surplus” and opened them for non-Indian settlement.

Section 5 of the Dawes Act required the United States to “hold the land thus allotted, for the period of twenty-five years, in trust for the sole use and benefit of the Indian to whom such allotment shall have been made…”

During the trust period, individual accounts were to be set up for each Indian with a stake in the allotted lands, and the lands would be managed for the benefit of the individual allottees. Indians could not sell, lease, or otherwise encumber their allotted lands without government approval. Where the tribes resisted allotment, it could be imposed. After twenty-five years, the allotted lands would become subject to taxation. Many allottees did not understand the tax system, or did not have the money to pay the taxes, and lost their lands and European settlers were waiting to scoop them up for next to nothing.

The early Indian trust system evolved from a series of adjustments to a policy that was gradually abandoned, then finally repealed. The allotment regime created by the Dawes Act was never intended to be a permanent fixture; it was supposed to transition gradually into fee simple ownership over a period of 25 years, about one generation. The theory that Indians could be turned into farmers, working their allotted lands was folly, not the least because much of the land they were allotted was unsuitable for small family farms. Within a decade of passage of the Dawes Act, the policy began to be adjusted because of government concerns about Indian competency to manage land and avoid predation by unscrupulous settlers. As late as 1928, the overseers were extremely reluctant to grant fee patents to Indians – the Meriam Report of that year advocated making Indian landowners undergo a probationary period to prove competence.

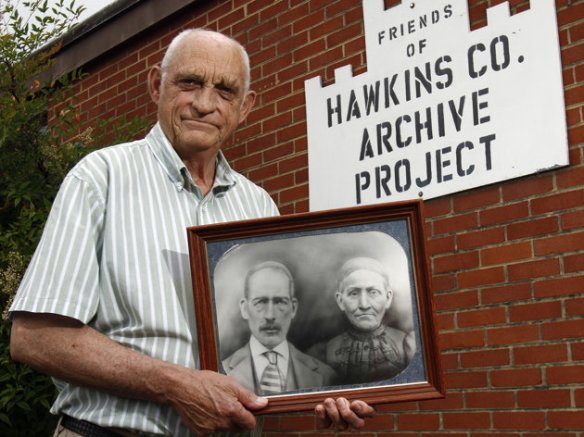

By passage of a series of statutes in the early 1900s, the government’s trusteeship of these lands increasingly was made a permanent arrangement; Interior’s trusteeship is sometimes referred to as an “evolved trust.” Little thought was given at the time to the consequences of making permanent the heirship of allotments. Lands allotted to individual Indians were passed from generation to generation, just as any other family asset passes to heirs. Probate proceedings commonly dictated that land interests be divided equally among every eligible heir unless otherwise stated in a will. As wills were not, and are not, commonly used by Indians, the size of land interests continually diminished as they were passed from one heir to the next. An original allotted land parcel of 160 acres may now have more than 100 owners. While the parcel of land has not changed in size, each individual beneficiary has an undivided fractional interest in the 160 acres.

The allotment policy was formally repealed in 1934, with passage of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 (IRA). However, the wheels already set in place continued to turn until the lawsuit was filed in 1996.

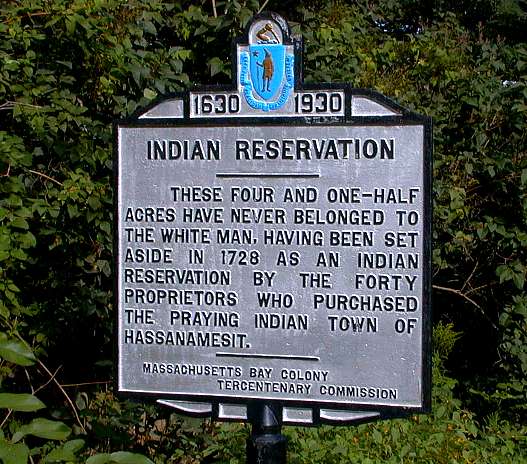

If you thought that the Indians “owned” the reservations outright, they didn’t. Even in earlier circumstances, in the early 1700s in North Carolina, the Tuscarora Indians were required to obtain approval of the legislature before they could “sell” their reservation lands. By that time, there had already been too many examples of Indians being taken advantage of, especially after becoming under the influence of alcohol, and signing their lands away. In addition, they didn’t understand the concept of value in terms of monetary value as compared to similar land elsewhere. Unethical people were all too willing and ready to take advantage of the Indians, often under the guise of “brotherhood,” so these laws were originally put in place to protect them, both from those who would be less than honest with them as well as from their own ignorance of white man’s society.

Hat tip to Rod for the link to the Cobell Case article.