Kokomo, Indiana is named for a Miami Indian named Kokomo. That much, everyone agrees about, but that’s the extent of the agreement. Beyond that, legend reaches in both directions. One version of the legend of Chief Kokomo states that he was kind and was venerated by the selection of Kokomo as the name of the town where he lived. More legends, in fact, most legends tell a different story – one less venerating, of a hard-drinking, rabble-rousing, trouble-making, wife-beating malcontent who was expelled from the Miami tribe in Miami County, and took up residence with a few followers in what would become Kokomo.

Reaching back in the records, we find that David Foster, the man who founded and plotted the city of Kokomo said of the place, “”It was the ornriest town on earth, so I named it for the ornriest man I knew — called it Kokomo.” Was that said in jest? We have no way of knowing – but given the number of similar stories – likely not.

One story tells that Kokomo, in addition to being quite fearless and outspoken, was an extremely large man, towering over everyone else in town. In fact, when (unmarked) Indian burials were disturbed in 1848 when a sawmill was being built near the old location of the Indian village, one was identified as that of Chief Kokomo because of the extremely large size of the bones. Apparently Kokomo was then reburied, along with all of the other Indian bones that had been inadvertently disturbed, together in a pine box, in the old pioneer cemetery, a couple of blocks away.

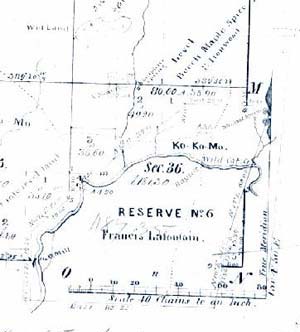

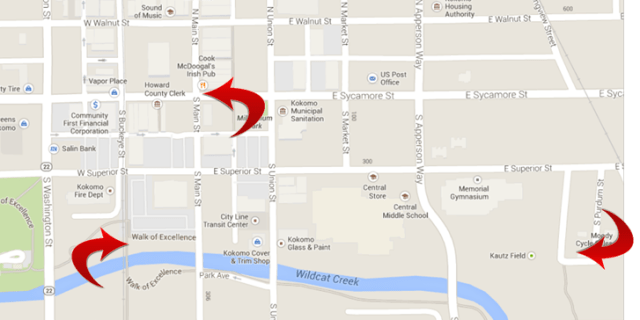

In the late 1840s, this tract was awarded to Miami Indian Chief Francis LaFontaine. In fact, there is a street in this area of Kokomo today named LaFountain street. You can see the word “Ko Ko Mo” where the village was located. The village is near present day Main and Sycamore Streets. Buckeye south of Superior, on the banks of the Wildcat Creek, where the burials were discovered, is a block or two away, on the other side of the courthouse and slightly south. Today, this is all downtown area of Kokomo.

On the contemporary map above, the Indian village is the top arrow, the original location of the Indian burials is the bottom left arrow and the Old Pioneer Cemetery where Kokomo’s remains were reburied is at far right.

Kokomo, whether chief or rogue, or both, lived in the 1830s and was probably dead by the time this land was granted to Francis LaFontaine in the later 1840s. We know that Kokomo was alive in 1840 when a gunsmith was repairing his gun and Kokomo decided he wanted to kill the man because he was a Kentuckian and Kokomo has been cheated previously by a Kentuckian.

The only actual record we have of Kokomo is a record from a trading post.

Chief Francis Godfroy maintained a trading post at the mouth of the Mississinewa River back in the 1830s. One entry in his store ledger on Wednesday, June 27, 1838, when “Koh Koh maw” and a squaw were billed $12 for a barrel of flour and a few yards of Calico. Most Indians also bought Whiskey which sold at .25 a quart, but Koh Koh Maw has no record there of buying whiskey. This does not support the reputation as a drinking man, although clearly, it is only one record.

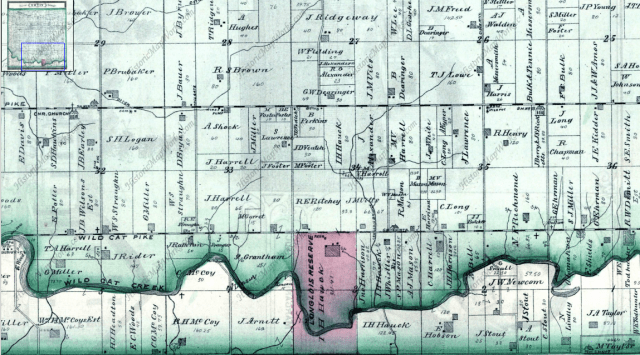

There were other Miami Villages in this general region as well, based on the 1877 Howard County Historical Atlas. Nip Po Wah lived at Vermont and Shoc Co To Quaw at Greentown. Pete Cornstalk lived at Indian Suck (the southeast corner of Ervin Twp.) and Ma Shock O Mo south of Greentown a mile and a half; Shap Pau Do Sho which meant “Through and Through,” was at Cassville.

The Ervin township location is shown on this 1877 map. I believe it is the pink tract shown below.

http://www.historicmapworks.com/Map/US/22645/

However, only Kokomo had the honor of having a town, now a city, named after him.

Kokomo’s reburial location is marked today in the old Pioneer cemetery.

This old photo shows the location in the 1900s with a memorial honoring both the old pioneers and Chief Kokomo who is buried along with them. I surely wish they would mark the location of the Native cemetery along the riverbank of the Wildcat Creek.

You can read more about Kokomo, the Indian, at these links.