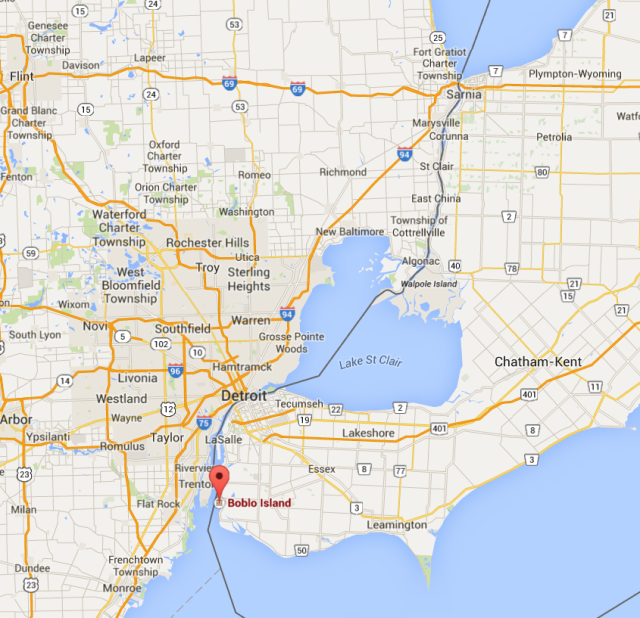

This map shows the metropolitan Detroit area that is relevant to the discussion of the Indian trading, slavery and burials in this article. The red balloon is Boblo Island in the river between Detroit and Windsor, on the Canadian side.

From the French Canadian Heritage Society of Michigan, we find the following important contributions to understanding early Indian slavery in the Detroit River region, an important trading area.

http://www.habitantheritage.org/french-canadian_resources/parish_records

To begin, Suzanne Boivin Sommerville writes about the Panis Indian burials at St. Anne Church in Detroit

http://habitantheritage.org/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/Panis_Indians_-_Suzanne.342145017.pdf

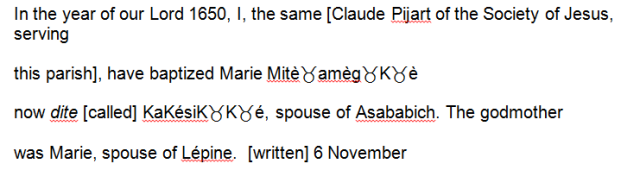

I noticed that these 212 burials have Christianized first names, which surely were given during the Catholic baptism, but only a handful had surnames and those were generally children of Frenchmen and Native wives. I asked if this was the norm and Suzanne replied with this example from her published works:

“The 1657 marriage record of Pierre and Marie is not, however, the first documented reference to Marie. Her baptism record, almost seven years earlier, survives in the registers of Nôtre Dame de Montréal. This text is also in Latin. Jean Quintal sent me a photocopy of the entry along with his Latin transcription and a French translation, which I here translate into English:

The symbol I represent with the Wingding for Taurus, is really a digraph used by the priests and other officials to represent a sound often “printed” as an /8/ and the sound is either /ou/ or English /w/ before a vowel. PRDH transcribes it always as /ou/, so to continue from my article:

“Before her baptism, Marie had used another Indian name, KaKésiKKé, or KaKésiKouKoué; but, apparently following the Indian tradition of taking a new name at important moments in life, she adopted the name Mitéouamegoukoué, and accepted her godmother’s first name, Marie, as a Christian first name, thus adopting a tradition of the Roman Catholic Church. Her daughter Isabelle would also adopt a new name, Madame Montour, at a crucial time in her life after the death of her brother, Louis Couc dit Montour. At Marie’s baptism, she was the wife of Asababich, also an Indian. She had at least two children by him, both of whom were baptised at Montréal and appear to have died before her marriage to Pierre Couc.”

The ending “Koué” eventually evolved into “squaw” in English, and means woman.”

Suzanne goes on to provide some additional information on the naming practices of the Hurons and Wendats.

“From my Couc / Montour saga available on a CD on the FCHSM website:

The Jesuit Relations report these missionaries’ understanding about Indian names. Since the Jesuits were educated linguists of some skill, as well as first-hand witnesses of Native traditions, it is worth quoting part of one of their relations at length, in this case concerning the Hurons / Wendats:

OF THE MISSION OF SAINT JOHN THE BAPTIST AMONG THE ARENDAENHRONON.

In this Country, there are no Names appropriated to Families, as in Europe. The Children do not bear their Father’s name, and there is no name that is common to the whole Family,- each one has his own different name. Nevertheless, it is so arranged that, if possible, no Name is ever lost; on the contrary when one of the Family dies all the relatives assemble, and consult together as to which among them shall bear the name of the deceased, giving [page 165] his own to some other relative. He who takes new name also assumes the Duties connected with it, and thus he becomes Captain if the deceased had been one. This done, they dry their tears, and cease to weep for the deceased. In this manner, they place him among the number of the living, saying that he is resuscitated, and has come to life in the person of him who has received his name, and has [121 i.e. 119] rendered him immortal. Thus it happens that Captain never has any other name than that of his predecessor, as formerly in Egypt all the Kings bore the name of Ptolemy.

Therefore, as this election of the Captains, or (as the Hurons say) the resurrection of the dead, is always celebrated with pomp and splendor, when it became necessary to bring back to life the brother of this new Christian,—that is, when new Captain had to be elected,—all the chief men of the Country were called together; and we also were invited, as to [sic] Ceremony in which the French were greatly interested because it was question of reviving the name of Atironta, he who had formerly been the first of the Hurons to go down to Kebec [sic], and to form friendship with the French. When the Nations were assembled, they conferred on us the honor of selecting him whom we wished to assume that name and the office of Captain. We deferred the choice to the discretion and prudence of the Relatives. “We therefore,” said they, “cast our eyes on that man,” pointing out Jean Baptiste to us; “and we do not wish his name [122 i.e. 120] to be any longer Aëoptahon but Atironta, since he brings him back to life. [1]”

The tradition of Native people changing their names at important times in their life is not restricted to the tribes near Detroit. One of the first records we have of Native people in what would become the United States is Sir Walter Raleigh’s Lost Colony on Roanoke Island in what is now North Carolina, beginning in 1584. The 1587 Colony itself may have eventually been “lost,” the but the journals of the first military expeditions to the island remain and those men record that one of the Native men changed his name from Wingina to Pemisipan.

Search the links below for Native burial records transcribed by Gail Moreau-DesHarnais for the word “panis,” “mitis” and “sauvage” to find the Indian burials.

Ste. Anne’s (Detroit, Michigan): Part I (1706 – 1751); Part II (1751 – 1766); Part III (1766 – 1776); Part IV (1776 – 1787); Part V (1787 – 1793); Part VI (1793 – 1799); Part VII (1800 – 1805)

St. Jean Baptiste (present-day Amherstburg, Ontario) and St. Pierre / Peter (present-day Tilbury, Ontario): Burials to 1805

L’Assomption-de-la-Pointe-de-Montréal-du-Detroit (Assumption in present-day Windsor, Ontario): Part 1 (1768 – 1784); Part 2 (1784 – 1792); Part 3 (1792 – 1800); Part 4 (1800 – 1805).

Many of these panis were young or newborn children, so they were obviously being born to a panis mother and a father who could have been Native or not. In some cases, there is no name for the child or the mother, only the owner.

In addition, the French Canadian Heritage Society provides a link to other Native American resources of the region.

http://www.habitantheritage.org/native_americans

Another valuable link is this one to French Canadian and Native Families.

http://habitantheritage.org/native_americans/french_canadian_and_native_families

In addition, there was a 1762 census of this region that includes information about Native people and slaves.

I had asked Suzanne about an entry within the burial records that referred to “rivierre Panisse,” as a place name.

Here’s what she found.

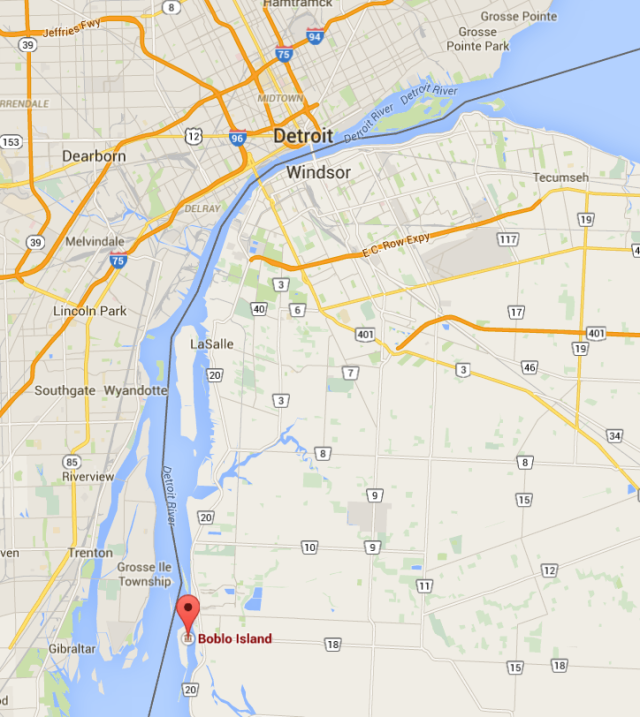

I found the reference I wanted for the riviere de la panisse: Page 9 of Diane Sheppard’s article, Census and Land Records, shows the original Chaussegros de Léry Maps. In the first one, point M is identified as riviere de la panisse. This is approximately just south on the Ontario side of the current Ambassador Bridge that links Detroit and Windsor. The area near the Ontario side of the modern bridge was occupied by the Huron from 1748 on before they gifted the property to build Assumption Church. The University of Windsor is now there also. These Huron Petun who came to be called Wyandot had originally settled close to Fort Pontchartrain at the invitation of Cadillac, just downriver from it, on the North shore, until they moved to Isle aux Bois Blancs (Bob-lo Island) up to the point that the rebel Huron destroyed that settlement in 1747.

The area on the USA side not far from the Ambassador Bridge had been occupied for many years by the Potawatomi, also invited to settle near Fort Pontchartrain. They also gifted that land to French Canadians.

On the map below, the Ambassador bridge is the only surface link between Detroit and Windsor until you get to Port Huron, another hour north where a second bridge is located. Ste. Anne’s Church in Detroit sits at the foot of the Ambassador bridge on the Detroit side.

I asked Suzanne about when slavery ended in this region.

She replied:

Wikipedia says ” Slavery remained legal, however, until the British Parliament’s Slavery Abolition Act finally abolished slavery in all parts of the British Empire effective August 1, 1834.”

See also http://www.historymuseum.ca/virtual-museum-of-new-france/population/slavery/

The abolition of slavery:

In the Louisiana region, slavery was not abolished until 1865, but the situation was entirely different in Canada where, by the 18th century, to the use of slaves was becoming increasingly infrequent. In 1793, Upper Canada (today, Ontario) legislated for the first time against the importation of slaves, thereby heralding the gradual elimination of slavery. The same year, Lower Canada (Quebec) also presented a bill to abolish slavery. Several members of the Legislative Assembly, themselves slave owners, opposed the legislation. Finally, it was the courts who sealed the fate of slavery in the province: in various cases concerning the arrest of slaves for having run away from the domicile of their master, judges ordered the liberation and manumission of the fugitives. In 1833, the official abolition of slavery in the British Empire simply confirmed the existing status that had already prevailed for several years in Canada. However, it is impossible to state with precision the date when slavery disappeared from the country.

I want to thank Suzanne for answering many questions during the preparation of this article and so willingly sharing her years of expertise.

Hello Roberta, since this post dates back t 2014 I am not certain if you are still active in research regarding the Panis on the Canadian side of the Detroit River or not, However, if you are able to read this message I most want to say THANK YOU!! Thank You to Suzanne Sommerville for sharing so generously also – especially for honouring the heritage of the original peoples of the Windsor-Detroit region, not just because I am a descendent of these peoples, simply because their stories deserve to be told. Beyond this acknowledgment, if / when I get a reply to this introductory reply, I have much I would like to discuss with you as I am currently doing a Master of Education relating to the Panis of ‘riviere de la panisse’ wherein I have resided since 1975.

P.S. None of the links (below) to these burial records are working, So can you provided me with alternative means of acquiring the knowledge?

St. Jean Baptiste (present-day Amherstburg, Ontario) and St. Pierre / Peter (present-day Tilbury, Ontario): Burials to 1805

L’Assomption-de-la-Pointe-de-Montréal-du-Detroit (Assumption in present-day Windsor, Ontario): Part 1 (1768 – 1784); Part 2 (1784 – 1792); Part 3 (1792 – 1800); Part 4 (1800 – 1805).